American Individualism in the Apocalypse Genre

Doomsday prepping has become more and more prevalent in the United States, encouraged by the COVID-19 pandemic, the anticipation of the earthquake along the San Andreas fault, and the general distrust of the government by citizens from most angles of the political compass. This cultural climate, aided by mainstream entertainment’s portrayal of survivalists, has validated some of the darker feelings of the conservative American public, notably the instinct to protect one’s land, family, and resources over all else.

Survivalists, once the butt of tin-foil hat jokes, are now fairly understood in most circles. Whether you took it up as a hobby to simply build practical skills, live out your back-to-the-land fantasy, establish yourself as a community leader for times of disaster, or are convinced that “we’ll need this bunker someday when the Feds come to take our guns”, you will be able to find a community online who shares the same sentiment.

Survivalism in Entertainment Media

TV shows like Man vs. Wild and Survivor popularized audience interest in survivalism despite the obvious lack of realism. Man vs. Wild is a particularly interesting case, as Bear Grylls admitted that it was a “worst-case scenario show… of course things have to be planned. Otherwise, it would just be me in the wild and nothing happening, you know, ’cause textbook survival says you land, you get yourself comfortable, you wait for rescue…” This shows the dramatization of survival scenarios in the public eye and the potentially heroic aspirations of those who admired Grylls’ stunts without realizing how unlikely it would be for the average American to be in his specifically designed situations.

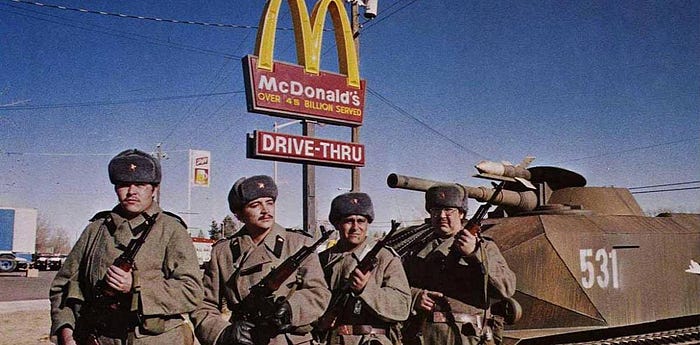

Moving on to explicitly fictional video entertainment, one can easily find doomsday prepper characters in various genres. From Red Scare-influenced patriot flick Red Dawn, classic 90s monster movie Tremors and its Gummers’ basement armory, and horror film A Quiet Place’s valiant survivalist father, it is clear that according to Hollywood, when disaster strikes, those who are prepared are the most likely to live. While telling distinct stories, all three revolve around a major catastrophe: Red Dawn being a World War III story about a group of teenagers who fight invading Soviets and Cubans by using guerilla warfare in Colorado.

This film resonated with a specific audience, earning a #15 spot on the National Review’s “Best Conservative Movies List” and gaining applause from the Gun Owners of America: “(for) dramatically depicting the importance in our time of the Second Amendment.” (Los Angeles Times, 1985.) A review of the film from the Austin Chronicle said that many of the audience members in the theater were “19-year-old gun nuts” and that “One commented to us before the movie started that he was there to check out the Soviet military hardware and ‘to see Ivan get his.’” Red Dawn, while laughable now as a paranoid militaristic vision, still validates the fear of some; that America could be invaded and isolated from its allies, leaving civilians to defend their home soil and restore patriotic justice. Though this plot doesn’t explicitly call for Americans to become preppers, it strengthens a nationalistic mindset and vouches for a strong gun culture, two elements of survivalism that can turn to something more sinister, such as right-wing militia involvement.

Tremors, on the other hand, is much more lighthearted. The campy Western-themed horror-comedy relies on a survivalist couple to save the day from monstrous worms called Graboids. These characters defend their property and fight the monsters with illegal weapons such as homemade bombs and an elephant gun. Though the couple separate later in the series, Burt remained a fan favorite for his eccentricity and tough-guy attitude and has starred in many of the sequel movies. He’s also spawned quotable moments like “trick or treat, you son of a bitch” and “broke into the wrong goddamn rec room, didn’t you, ya bastard?” Strangely enough, the actor, Michael Gross, was inspired by Burt’s ability to fight giant worms and became a prepper himself. According to an LA Times article titled “Movie Turns Wimp Into Survivor”, Gross describes his earthquake-proofed house and says that he “went to a survivalist bookstore . . . and bought some bumper stickers that I thought would be perfect for Burt. You know, things like ‘Don’t Forget Our MIA’s’ and ‘America Is Worth Fighting For’”.

A Quiet Place makes a very strong case for doomsday prepping as a post-apocalyptic film where deadly aliens with enhanced hearing have wiped out most of the human population. The protagonists are a nuclear family who have designed a homestead to suit their needs, which most importantly is maintaining silence for survival and because they have a baby on the way. The father, Lee, is a stereotypical man’s man: handsome, fit, bearded, skilled in all practical matters, and protective of his family at any cost. Throughout the movie, viewers see Lee’s intensive and successful efforts to keep his wife and kids safe and may have left the theater wondering if they should start putting together a bug bag or get their firearms license themselves. Overall, the story is exhilarating and showcases that tight-knit families with practical backgrounds in rural areas are the best suited for surviving cataclysmic events.

John Krasinski, director of A Quiet Place, created this film as “a metaphor for parenthood” but got both praise and criticism from others based on apparent political themes. Robert Barron, a Catholic Bishop, was happy to perceive the family’s decisions as pro-life, while Richard Brody of The New Yorker complained of the plot’s encouragement of gun culture. While I am inclined to defend Krasinski’s original message, the movie is clearly visible to others as a white survivalist fantasy.

A Quiet Place II is an interesting case because the family is not alone in their survival efforts. The Abbotts join up with their former neighbor Emmett, but (spoilers ahead) because Lee dies in the first movie, Emmett could arguably serve as his replacement here as a white male patriarch to complete the nuclear family once again. Additionally, even though the household reaches an island community of survivors, there is no sigh of relief because Regan and Emmett have led one of the aliens to the island and it wreaks havoc on the colonists. The community leader is killed while trying to aid the main characters, subconsciously asserting the trope that those who stop to help others in an apocalypse will suffer for their empathy.

Competition / Scarcity

Apocalyptic movies tend to present audiences with an “us vs. them” scenario: humans versus zombies, gangs versus other gangs, civilians versus The Government, or the moral versus the immoral, which can take form in cannibals, thieves, or anyone who otherwise lost a piece of their humanity from showing weakness in the face of disaster. Media can ease viewers with survivalist characters, who act as the “moral” ones. They are the levelheaded, rational foils to the classic end-times villains who loot TVs out of storefronts and gleefully commit homicide à la The Purge. These tropes imply that society is masked by a thin layer of civility and that most people are secretly waiting for a chance to commit crimes and bask in anarchy when given the chance, confirming fears of “Thin Blue Line” supporters. When presented with political unrest and an uncertain economy like we’re facing now due to the pandemic, climate crisis, growing class divides and more, it is understandable to feel stressed and want to prepare for the future. The one thing to remember is that fictional survivalist characters are not role models, and plots of sci-fi/horror films are unlikely to bear any resemblance to the kinds of disasters we may actually see in real life.

Unfortunately, the survivalist motives exhibited by movie characters don’t lend themselves well to a sense of community in the face of danger — prepping for disaster often devolves into selfish stockpiling, as we’ve seen just last year with the COVID-19 pandemic. Hand sanitizer and toilet paper were bought at alarming rates, in some cases sold for huge markups. Media in the apocalypse genre has rewarded characters who reflect the value of American individualism by making heroes out of those who hoard instead of sharing with “untrustworthy” outsiders. Uncomfortably close to the plot of a virus horror movie, during the height of COVID-19 in the United States, we all saw ourselves prioritize personal safety and the safety of our loved ones, sometimes instead of the well-being of our community as a whole.

To challenge this dismal view, political writer Rebecca Solnit, in her book “A Paradise Built in Hell”, argues that disasters may actually bring out the best in people and awaken a sense of compassion and community that was previously hidden in the status quo of neoliberalism. In an article she wrote for The Guardian, she explains that while the pandemic brought up some ugly aspects of humanity (the aforementioned stockpiling and re-selling), it also saw an overwhelming rate of mutual aid, volunteering, and community networking. Even when times were overwhelmingly dark with high unemployment and COVID-19 transmission rates, we found ourselves able to help each other, even just in small ways like sewing masks for hospital workers or delivering food to elders.

Solnit also writes in her article that since we live under a capitalist system, competition and scarcity are ever-present, so it is only natural for us to see the end of the world as having winners and losers. In order to break free from this mindset, we need to see each other as the neighbors that we truly are instead of the competitors that our economic system wants us to be. Even for those who live in rural areas, knowing who lives near you and exchanging information could save a life in case of an emergency. While writing about the long-term effects of the pandemic, Solnit predicts that “It seems likely that conservatives will argue for brutal austerity and libertarian abandonment of the most desperate, while the rest of us are going to have to argue for some form of post-capitalism that decouples meeting basic needs from wage labour.” The survival-of-the-fittest mindset has no place in discussing basic needs such as food, shelter, and healthcare, and it is cruel to suggest that in a time of crisis, those who are underserved in regular society should be subject to even more obstacles.

An article from The New Yorker, “Doomsday Prep for the Super-Rich”, details how an alarming amount of affluent Americans, most in the Silicon Valley tech industry, are buying properties to escape to in case of some spectacular societal breakdown. Even more disturbing is the fact that some of them are banding together to become allies in what they expect to be a long-haul scenario. One man who used to work for Facebook is quoted saying: “All these dudes think that one guy alone could somehow withstand the roving mob… No, you’re going to need to form a local militia.” This phenomenon is perhaps more unnerving than right-wing preppers hoarding guns, because it seems like those who hold power and influence are going to ride out any kind of crisis alone in their towers while the rest of us, the “mob” in question, kill each other for basic necessities.

Why Does Media Matter?

As frightening as this all sounds, it’s vital to note that most apocalyptic narratives are exaggerated or even fantastical, often straying into science fiction rather than speculative fiction. They’re dramatic and hyperbolic because it makes for good entertainment, and that makes survivalism the paranoid cliche that it is. Fiction in this genre is supposed to be exciting and far-fetched, allowing for a distanced sense of escapism from everyday life. The problem arises when this starts to feel like a real impending future for some, and they expect every street protest to tip the scale into societal chaos, they become antisocial or aggressive, or worse, try to intentionally speed up a conflict like the accelerationist Boogaloo Boys.

It is also important to note that some communities have been living through crises for years; on the topic of apocalyptic fiction, Potawatami scholar Kyle Whyte says in an essay: “Yet for many Indigenous peoples in North America, we are already living in what our ancestors would have understood as dystopian or post-apocalyptic times. In a cataclysmically short period, the capitalist–colonialist partnership has destroyed our relationships with thousands of species and ecosystems.” This reality, faced by many Indigenous groups because of colonization and environmental/climate injustices, makes it all the more inappropriate that gun-toting stockpilers seem to be cosplaying some kind of Mad Max-style dystopian future while some tribal reservations already currently face clean water scarcity.

Overall, survivalism is not inherantly conservative; people from all across the political spectrum are interested in preparing for the worst, myself included as a leftist. Ideally, we won’t live through an event that shatters our government, but seeing disasters that the government has bungled even while being present, like Hurricane Katrina or COVID-19, it may be partly up to us to take care of one another, especially when certain groups are impacted harder than others. I agree with Solnit in that disasters should bring out the best in us. I believe we need to build strong communities that are able to withstand crises, big or small, and that means a lot of skillsharing, communication, and love. Weapons aren’t the only necessity in an emergency, we will need people to farm, to build shelters, to delegate, to caretake and counsel. This means all ages, all abilities, all experiences are welcome and valuable. In a realistic emergency, those will be the folks who fare the best, not the lone wolves with their basement arsenals.